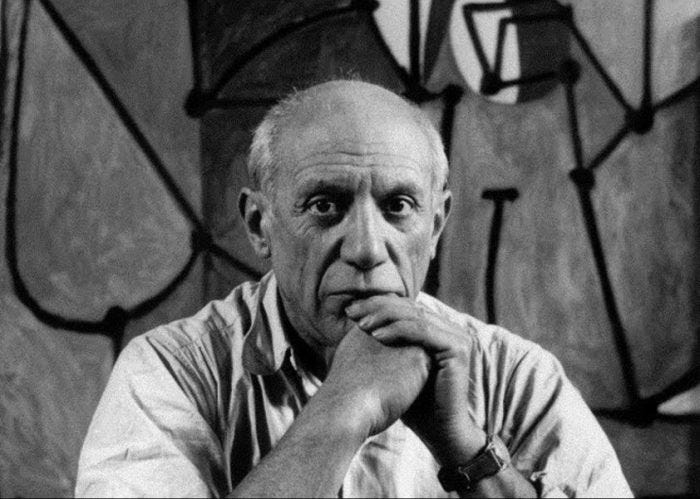

How Picasso Hacked Willpower to Produce 50,000 Works of Art

A study on willpower… and whether it really works.

In 1895, had his sister not died, Picasso may never have picked up a paintbrush again.

He had made a pact with God. At age 13, he promised to give up his gift if destiny saved her.

Although an atheist in later life, it’s been suggested that the outcome of this episode reinforced his famous conviction in his abilities. Art was his calling, and even at an early age, Picasso not only showed prodigious talent but he also never doubted that he would be great.

There’s an old myth of him sitting at a cafe in Paris when a woman recognized him and asked him if he would draw up a quick piece on a napkin for her.

Humoring her, he agreed.

“That would be $1 million,” he told her, once he was done. Confused and taken aback, she pointed out that it had taken him only 30 seconds to draw.

He responded:

“No, my dear woman, you are mistaken. It took me 30 years to draw that in 30 seconds.”

Over the years, it’s estimated that Picasso produced up to 50,000 works of art, ranging in form from paintings and drawings to ceramics and tapestries. That’s more than one piece a day from the moment he was born.

The man dedicated his life to his craft, and he had a lot to show for it. Although talent played a role in his legacy, the larger story behind his success was his commitment and work ethic.

Any conversation on long-term dedication flirts with the topic of willpower. It’s a prerequisite for hard work, and there are elements of Picasso’s life that show us how it works and how we can use it to our advantage.

What is Willpower?

In simple terms, willpower is the ability to resist short-term gratification for a long-term goal.

It’s at play when you go out of the way to avoid the temptation of a cookie while on a diet, for example, or when you choose not to procrastinate in the face of a deadline.

To understand the concept, however, it’s important to know why this conflict occurs in the first place. It appears to be a product of what psychologists call a dual process in our mind.

The best distinction is presented by Nobel Prize-winning behavioral economist Daniel Kahneman in his book, Thinking, Fast and Slow. He describes System 1 as an automatic processor, mostly unconscious, that uses emotions to make quick decisions. He labels System 2 as a controlled processor, fully conscious, that makes rational choices over time.

System 1 is an old primitive operation that’s concerned with short-term gratification, while System 2 is a more recent outcome of evolution that’s concerned with long-term planning.

Although modern civilization works mostly with emphasis on the long-term, we still operate with parts of the same brain that relied on short-term thinking to survive and to reproduce in our early existence. It forces a battle, and that’s why willpower is something we talk about.

The Power of the Primitive Mind

As a kid, Picasso was a bad student. An art prodigy, sure, but not very focused on anything else. He couldn’t bring himself to do the work because all he wanted to do was paint.

On some level, both studying and painting involve a delay in short-term gratification, but for Picasso, painting never felt like a compromise — whereas studying did — because he loved it.

The most effective way to stick with a long-term goal is actually by harnessing the power of our primitive mind. System 1 is quick and reactive. It’s in the driver’s seat, and it’s what makes self-control difficult. But if you can connect your long-term goal to deeper emotions, you can trick the old evolutionary mind to work for you. That’s what Picasso did.

If you use the reasoning ability of System 2 to emotionally frame your long-term goal, you can overpower the other impulses that System 1 throws your way when it gets challenging.

This also explains why people talk about passion when it comes to success.

Is Willpower Limited?

One of the most cited concepts in behavioral psychology is the theory of willpower depletion.

In 1998, Roy Baumeister and Dianne Tice did an experiment at Case Western Reserve University on student volunteers which first presented the idea that willpower is limited.

Since this experiment, many studies has been done to support a similar result, including a meta-analysis in 2010. It’s something that’s widely believed, and it appears to be verifiable.

Recently, however, another two meta-analyses showed something else. The authors included many previously unpublished studies in their breakdown, and they actually found no material correlation. They concluded that the theory of willpower depletion lacks significant support.

The implications of this are interesting. Right now, it’s hard to say where we stand. It might be years before we have a conclusive answer. That said, there may be a different way to look at it.

The Influence of Mindset

Psychologists from Stanford and the University of Zurich have conducted a number of experiments that show a correlation between self-control and the belief we have about its limits.

In their studies, people who thought that they had limited reserves of self-control did indeed show signs of willpower depletion. Those who went in with the mindset that self-control is self-renewing — hard work paves the way for more work — showed no signs of slowing down.

More convincingly, however, when some of the subjects were taught that willpower wasn’t limited, these subjects appeared to show an increase in their capabilities. They found fewer excuses to give in to temptation and their decisions better aligned with long-term benefits.

Take Picasso, for example. We can reason that there was likely a strong link between his conviction in his abilities and his incredible output. When it came to painting or drawing or other crafts, he never seemed to compromise for the short-term gain of procrastination.

He genuinely seemed to believe that he was put on Earth to make art, so he got up every morning in his adult life and put in the work to create two or three, and sometimes, more pieces of work. That’s an unparalleled production rate even among the greats. He likely had his own distractions and temptations, but they just didn’t seem to matter.

The scientists behind this new theory of willpower don’t necessarily see willpower as unlimited but as nonlimited. There are still things that affect how we function, like food and rest, but we have good reasons to believe that, to some degree, mindset and abilities go hand-in-hand.

External Motivators and Momentum

Regardless of whether or not we have an infinite source of willpower, there are times when it’s still difficult to harness. Research has shown this again and again, and we can’t attribute all of it to the limitations of our mindset. Sometimes, what we need an external motivator to inspire momentum.

Using environment design is one part of it. By making our environment more compatible with habit forming behaviors, we can limit the amount of willpower that we need to use. The second kind of external motivator is the influence of others, especially when it comes to commitment.

This is something Kelly McGonigal advocates. She’s a professor at Stanford University and the author of The Willpower Instinct. She’s found that, for example, when two people commit to a gym schedule, both parties are a lot more likely to follow through.

If you’re going by yourself, you might give in to a bad reason here and there, but if someone else is expecting you, you’re likely to go even when you might otherwise not have.

Along with Picasso, Henri Matisse is considered to be one of the great artists of the 20th century. Matisse was the early inventor of “ugly art,” and it’s said that one of Picasso’s greatest works, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, was directly inspired by the two men’s rivalry. Without Matisse in the picture, Picasso would likely never have painted his masterpiece.

Now, Picasso didn’t need to outsource his willpower by having Matisse in the picture, but Matisse’s presence had a huge influence on his behavior nonetheless. Our surroundings matter way more then they get credit for, and knowing how to use them is an advantage.

Research tells us that willpower is a better predictor of academic success than IQ, it makes you a more effective leader than charisma, and it’s seemingly even more important to a marriage than empathy.

Based on this, it’s not hard to see why it’s so crucial.

In many ways, the life of Pablo Picasso exemplifies what it means to be an artist. He was obsessed with his craft from the day he was born, and he had an unparalleled work ethic.

He may not actively have intended it, but a few central parts of his life act as a mirror for how willpower might play out in our own lives, and they give us a clearer understanding of how we can better use it.

If you have long-term goals, willpower matters. Learn to make it work for you.