The Reasons You Crave Sugar. Part II: From Fruits and Honey to Doughnuts and Candy

Organic Fitness: In the first article in this series on sugar cravings we established that humans have evolved a taste for sweetness; an evolutionary adaptation that benefitted our survival in an ancestral environment.

I also highlighted the fact that although the modern obesogenic environment – filled with cheap, sugar-laden junk food – is very different from the natural habitat in which we evolved, our ancient physiology is still with us. It’s therefore no surprise that so many people find it almost impossible to stay away from all the highly palatable food available.

Most of the articles on this notorious “sweet tooth” will simply leave it at that; implying that self-control and discipline are all that will help you avoid the freshly baked goods at the nearby 7-eleven. However, the story doesn’t end there. As mentioned in the last article, there are many unanswered questions, chief of which is why some people have an intense “sweet tooth” while others rarely feel the need to eat that extra portion of dessert after dinner.

Recently, a reader asked me the following questions in the comment section of one of my posts:

Hi Eirik!

I love your blog. Thank you for sharing your knowledge and passion with the rest of us- I am so thankful!

Also, I am wondering… did you ever have a “sweet tooth” that you had to overcome? I find this to be the most difficult part of changing my eating habits, I crave sugar. Have you found this to dissipate over time or were you genetically blessed in not having a hankering for it?”“Hi Rachel! I did actually have a sweet tooth. However, it’s pretty much completely gone now – unless I start eating something very sweet, then I feel the desire to eat more. I have an article on this very topic planned, and I hope to get it done as soon as possible. A “sweet tooth” is primarily caused by the effects sugar has on your brain and your gut microbiota …

Well, let me elaborate… I’ve been thinking about this whole thing for a long time. Are genetics (human)/epigenetic factors the reason some people are more drawn towards sugar-laden junk food than others? No, I don’t think so. These things do play a role, but not a major one. Basically, as mentioned in the reply above, I’m convinced that it boils down to the effects sugar has on our brain and gut microbiota. While the impact on our brain might be known to most people, the idea that gut microbes can influence our dietary preferences is probably more surprising to most people.

What I want you to keep in mind throughout the rest of this series on “sugar addiction” is the following phrase: “We crave what the body needs” (Or think it needs). I’ve already explained how this concept applies to protein. Basically, if you’ve ever gone a day eating very little protein, you’re going to feel a craving for this macronutrient. But, as you might be asking, how can this possibly apply to sugar? Why should someone who’s obese crave more sweets? Well, I’ll get to that in a while. First, let’s take a look at the changes that have occurred since the paleolithic era and how the modern food environment impacts us.

As mentioned in part 1, some paleolithic tribes and contemporary hunter-gatherer societies had/have access to plenty of sugar in the form of honey. However, these were clearly the exceptions rather than the rule. Also, while honey is definitely a very dense source of glucose and fructose, it is still a real food, meaning that it’s different from the refined sugars that now make up a large part of the western diet.

So, generally, the sweetest food available to our ancient ancestors was relatively sour fruit (compared to today’s standards), and even this source of carbohydrate was often relatively scarce. Okay, so where am I going with this? The food environment has changed dramatically. We’ve been able to create novel foods with an unnatural macronutrient composition and enhanced sweetness that our bodies aren’t adapted to handle.

The fact is that when people say they have a craving for sugar, it’s not really isolated sugar (e.g., glucose, fructose, lactose) they crave, but rather the processed westernized food that contains a combination of sugar, salt, starch, and/or fat. Because how many people really enjoy eating table sugar in itself? Not many. It’s the combination of highly palatable food ingredients that gets us.

Sugar-laden junk food overactivates the reward system in your brain

The reward system in our brain is responsible for reinforcing and motivating behaviours that favor the acquisition of desirable food. What does this mean? Well, let’s imagine that you eat a fresh doughnut right out of the oven. This piece of delicious baked good contains a wide spectrum of highly rewarding ingredients, such as refined wheat, sugar, fat, and salt, and it’s recognized as a safe and energy dense food. As we continue eating this food, we acquire a taste for it.

The combination of fat, starch, salt, and sugar is deadly.

Basically, these westernized products are not really food. They contain a nutrient composition that is completely different from that of natural food, and they have a higher reward value than anything we have consumed throughout our evolution. While the most rewarding foods available to our prehistoric ancestors, such as fatty organ meat and fruit, contain one fairly rewarding nutrient (fat or sugar), modern foods are hyper-rewarding in the sense that they contain several of these substances… And the food manufacturers know it. They know how to exploit our ancient physiology to their advantage by designing products that we essentially become addicted to.

Several studies now support the notion that these highly rewarding junk foods trigger a response in the brain that looks a lot like the events occurring in drug addiction (1,2,3). We essentially become addicted to food; and who can blame us? Ice cream and muffins provide a stimulus that is super-sized compared to what we are adapted to handle. This addiction is probably something a lot of people can relate to; the craving that happens at the sight of chocolate cake, the massive dopamine rush that occurs as you eat it, the downfall shortly after, and the increased desire for more at a later time.

This brings us back to the quote above; “We crave what the body needs”. Although the dopamine rush we get from eating a large piece of chocolate cake is fairly short-lived, the fact is that this food is both safe and calorie-dense, and it’s therefore no surprise that our body associates it with something good. Do you remember the picture from part 1, showing a child eating honey? Well, check out the rest of the pictures from this amazing journey into the mountains. These people put their life in great danger “just” to access a food they’re craving for.

Also, a diet heavy in these sugar-laden foods often leads to leptin resistance, increased body weight, and elevated energy needs, thereby further increasing our attraction towards calorie-dense food.

Okay, so I guess you can see that from an evolutionary point of view, our cravings for “junk food” make complete sense. But how does this relate to the initial question; why do some people have more of a sweet tooth than others? Well, it seems that people respond differently to these highly rewarding products. This is the same response we can see in all other parts of life. While some people essentially become addicted to social media platforms, others don’t feel this impulse to constantly check their twitter feed.

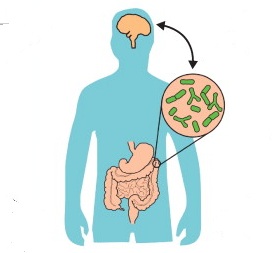

Bacteria are probably affecting your appetite and dietary preferences

The hyper-rewarding nature of doughnuts, chocolate cake, and ice cream isn’t the only problem with these refined products. As I’ve previously talked about, the gut microbiota – the collection of microorganisms that live in the gut – adapts to changes in environment and lifestyle. For example, if you change from a low-carb diet rich in animal source food to a high-carbohydrate diet rich in plant food, the gut microbiome will adapt to these dietary changes. The new environment in the gut will favor bacterial species that are involved in the digestion of plant polysaccharides, while microbes involved in fat metabolism will be less prominent. Basically, just like changes to the environment in a rainforest will impact the types of plant and animal species that are able to live there, environmental changes in the gut will impact the types of bacteria that are able to flourish. Okay you might say, but what has this got to do with sugar cravings? Well, what we’re now learning is that gut bacteria can probably affect the dietary preferences of the host. This might sound shocking to those who haven’t read up on the subject, but keep the following in mind: We are more microbe than human!

Let’s begin with a quote from a scientific paper:

Over three billion years of evolution have honed the capacities of bacteria to exploit their environments. Millions of years of coevolution of bacteria and their hosts have presumably selected those bacteria that best manipulate their hosts. It has been proposed that the species composition of the microbial organ influences the disease susceptibility of the host while, reciprocally, the host’s nervous system influences the species composition of the microbial organ. It has also been proposed that “changes in microbial diversity and hence the microbial organ, influence the function of components of the CNS (i.e., brain) as reflected in altered cognition”. One evident area in which feedback can occur is the link between cognition and nutrition. The issue has been raised as to whether “daily variables, such as food preferences, that determine homeostasis (could) be, in part, determined by a bacterial species that informs the brain, via the vagus nerve carrying information gathered by the neuronal elements innervating the GI tract, what it wants from a nutritional standpoint to survive”. In other words, the capacity of bacteria to adapt is such that if it is to their advantage to influence their host preferences for food, they will” (4).

Basically, the authors of the paper above present evidence showing that gut bacteria could affect our appetite and dietary preferences. This hypothesis is also supported by the following line of observations:

- Dietary shifts changes the composition of bacteria that live in the gut (5,6). Could it be a cycle?

- Other researchers than the ones listed above have also suggested that gut bacteria can influence nutrition-related behavior such as appetite (7,8).

- It’s well established that gut microbes affect the brain through the microbiome-gut-brain axis.

- “People who crave daily chocolate show signs of having different colonies of bacteria than people who are immune to chocolate’s allure” (9,10).

- Individuals with moderate-severe gut dysbiosis generally report intense food cravings and abnormal dietary preferences. This has been especially well documented in children with autism, ADHD, and other mental disorders characterized by gut dysbiosis (11,12).

- Obese and lean individuals harbor different gut bacteria. This doesn’t prove anything in itself, but it could be one of the reasons obese people often have an increased desire for “unhealthy” food.

- When people adopt a low-carbohydrate eating style, they often feel an intense desire for carbohydrates and sweets during the first couple of days. However, when they’ve been eating a low-carb diet for a while, these sugar cravings become less noticeable. Changes in gut microbe populations could be influencing these processes.

- Gut dysbiosis could interfere with the normal activity of the reward circuitry, thereby affecting our dietary preferences (11).

It’s already well established that gut microbes affect your mood and behaviour. Could they be controlling your appetite and dietary preferences as well?

If this hypothesis does hold true (as I’m convinced that it does), it has major implications for how we look at nutrition, obesity, and mental health. It’s likely that part of the reason some people have more of a sweet tooth than others is because their gut microbiota impacts their dietary preferences. It’s well-known that a diet rich in refined carbohydrates changes the oral microbiota and increases the risk of tooth decay. However, what we’re now learning is that a diet rich in sugar also changes the microbiota of the small intestine and that these alterations most likely increase your desire for more sugar. In mild cases, you might have few other noticeable symptoms than a desire for sweet food. Essentially, gut microbes could be controlling your appetite to their advantage.

Again, this entire idea might sound far-fetched for those who haven’t read the research, but the fact is that microbes are able to impact our mood, behaviour, and mental health. It isn’t unlikely that this interaction between host and bacteria also includes our appetite.

As mentioned previously in my articles; the data are very clear, the western lifestyle isn’t doing us any favors. Antibiotics, processed foods, caesarean sections, and a general disconnect from nature negatively impact the bacterial communities in and on our bodies, and many researchers are now talking about a westernized microbiome – a microbial rainforest that has lost the resilience and diversity of the microbiome of our ancestors. This is interesting in terms of appetite and dietary preferences because it could mean that cravings for processed junk food are partly driven by changes to the gut microbiota. In terms of heavy sugar consumption, these alterations would primarily take place in the small intestine.

All of this brings us back to the quote I mentioned earlier: “We crave what the body needs”. Microorganisms inhabit every area of our body that is exposed to the environment (and probably also other organs, such as the brain (12)), and they are very much a part of us. Actually, the gut microbiota is often referred to as the forgotten organ. So, it’s not just about what our human cells need, but also about what our bacterial cells need.

In the next (and last) part of this series on sugar cravings I’ll answer the three questions from part 1 and highlight some strategies you can use to turn this vicious cycle into a virtuous one…

All articles in this series:

The Reasons You Crave Sugar. Part I: A Taste For Sweetness

The Reasons You Crave Sugar. Part II: From Fruits and Honey to Doughnuts and Candy

The Reasons You Crave Sugar. Part III: Getting Out of the Vicious Cycle